Start your day with LAist

Sign up for the Morning Brief, which is delivered on weekdays.

C.College students have had to learn a lot of new pandemic-era vocabulary, but there is a term they coined that reflects a particular frustration they had while studying this year.

“Ghost Professor.”

“They don’t teach, you can’t see them, they don’t zoom, they don’t have office hours,” said Jonnae Serrano, a political science student at Santa Monica College. “I had office hours in which it was completely via SMS – I text my professor and wait for her to contact me.”

She and students at other Southern California community colleges complain about professors who gave them a list of YouTube videos made by someone else and questions as study material for the entire semester.

Other students described lecturers who did not start out as “ghost professors”, but rather went in this direction over the course of their distance learning.

“At first she was very active,” said Mt. Mayra Rivera, a student at San Antonio College, of a professor that semester, “but then she kind of faded … she’ll post the homework and her explanation was really good, but when it did You had a question … it barely answered in the end. “

Rivera got a zero for an extra credit allocation, she said, because the professor didn’t respond to her questions about submitting the paper, and by the end of the semester, that will likely mean the difference between an A and a B.

For other students, ghost professors contributed to a growing number of problems that made it difficult to stay in school.

A sign outside Santa Monica College

(Anthony Citrano via Flickr)

“I’ve gotten to a point where I honestly don’t enjoy school as much as I did when I just started,” said Susana Macias, a student at Pasadena City College. Before the pandemic, she enjoyed the large library on campus and personal interaction with students and lecturers during and after class.

She said a “ghost professor” in her history class held his camera away when she visited his online consultation three times.

“I just stopped doing it because it was only talking to a screen,” Macias said.

Lack of connection and interaction are the predominant themes among students who have described their experiences with “ghost professors”.

“I just want the teachers to be more present. If you want your students to work and be in your class, you should be there too, ”Serrano said.

Most of the students surveyed stated that they only had one or two “ghost professors” in this year-long distance learning course. The students said they don’t want to name the professors by name, but they think it’s important to talk about the experience to send a message to the university administration to make improvements.

The students give their universities input on teaching through surveys and evaluations at the end of the semester, but that may not be enough.

“There needs to be an actual conversation that goes beyond assessment and talks about what students are feeling,” said Natacha Cesar-Davis, professor of psychology at Diablo Valley College in the Bay Area and an expert on teaching at community colleges.

“Why do (students) say there are spirit professors? And those professors identified as such need to be followed up to understand their experiences, ”she said.

“Regular and substantial” interaction is a prerequisite

Both the state and federal government require higher education institutions that offer distance learning to concentrate on communication between teachers and students in order to “support regular and substantial interaction between students and teachers,” according to the accreditation commission for community and Junior colleges.

“That means a faculty member will initiate things like announcements,” said Mt. Meghan Chen, dean of library and learning resources at San Antonio College.

California regulations require distance learning teachers to have “regular effective teacher-student contact” by telephone, email, and through “one-on-one, orientation and review sessions, supplementary seminar or study sessions, field trips, library workshops”.

The Santa Monica College Library

(Courtesy Santa Monica College)

“The expectation is uniform. How local is defined is up to the institutions to clarify what they mean, ”said Chen.

The campus closure during the pandemic has resulted in lecturers spending a lot of time on the phone.

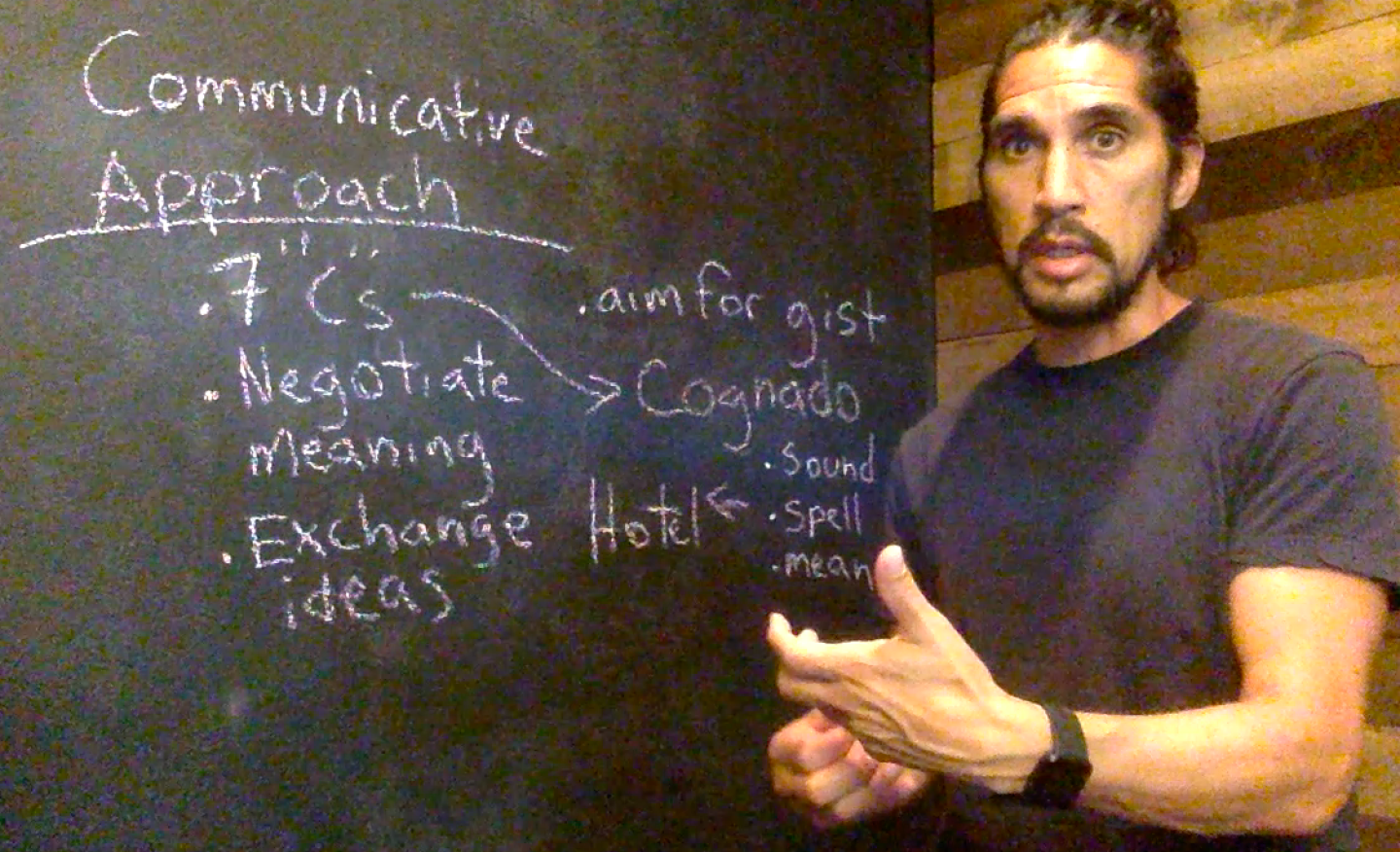

“I get in trouble at home because I connected my email to my phone. So I mostly reply right away, ”or early the next day if the news comes late at night, said Mt. Spanish professor Aaron Salinger of San Antonio College.

His approach has a lot to do with how he perceives his students to learn. Salinger believes student questions come when students are doing their job or thinking about their assignments.

“And the faster I can answer you, the more useful my answer will be. And even more so … they will be able to succeed, which is ultimately our goal, ”he said.

Universities are using new resources to train teachers

Berg San Antonio College is a community college in eastern LA County

(Courtesy Mt.San Antonio College)

Like other community colleges, Mt. San Antonio College trains its faculty in best practices for online teaching. The training had been around for years before the pandemic, and post-course certification was required to teach online courses. The pandemic threw all of that out the window. Certified or not, almost all faculties switched to online courses as they received emergency training from college and other faculties.

“It is important to note that the educators wanted a good online learning experience for the students,” said Chen.

She recommends students who have “ghost professors” to contact the department or department that oversees the subject.

“Because there is also the possibility… there is a reason the professor may or may not be available. And that’s another way of finding out what could happen, ”she said.

“When we are made aware of a situation where a teacher is unresponsive or does not have the necessary techniques to teach a class, we assess whether the person needs more training and / or simply more time with the students online must spend. “Said Jennifer Merlic, vice president of academic affairs at Santa Monica College, in an email. “After such an assessment, we react accordingly to the lecturer.”

During the pandemic, Santa Monica College offered over 40 training workshops that were attended by over 1,600 faculty, she said. And 276 faculties have completed online teaching certification courses lasting anywhere from two to eight weeks.

“On the very rare occasion when an instructor simply does not meet the requirements of the job, the class is reassigned to a different instructor,” Merlic said.

But the training can range from campus to campus. Some universities pay their teachers, including part-time staff, an education and some do not. Proponents say Sacramento lawmakers need to increase funds to provide training to all faculties to ease their transition.

“I felt and still feel overwhelmed,” said Manuel Sanchez, a Spanish professor at Pasadena City College.

Manuel Sanchez teaches Spanish at Pasadena City College

(Courtesy Manuel Sanchez)

He feels this way even though he was halfway through his nationwide online teacher certification at the time of the pandemic. He had incorporated online teaching methods, such as developing an online presence, for more than four years.

“To defend some of these so-called ghost professors, a lot of people don’t have the formal online training,” Sanchez said.

Prior to the pandemic, Sanchez said some of his students said they would choose classes based on ratings of this professor’s teaching style.

At Mount San Antonio College, a professor who receives multiple negative reviews or complaints from students may initiate an investigation by the professor’s academic department chair and the department’s dean.

“If research shows that a professor needs help under the contract, the professor should be offered additional training,” said Emily Woolery via email. She is president of the Mt. Faculty Association of the San Antonio Campus.

“Especially during COVID, when everyone was experiencing upheaval at work and at home, the faculty association wanted to make sure the faculty was treated with compassion,” she wrote.

Both Glendale College and Pasadena City College (PCC) said the faculty and administration worked hard to provide a strong educational experience during the pandemic.

A student resolution

In the first few weeks of the pandemic last year, a PCC spokesperson said the campus faculty passed a resolution recommending that “all faculty continue to ensure regular and effective contact and access to course materials.”

The PCC faculty passed a resolution on student engagement during the pandemic.

Some students have run out of compassion.

Malcolm Sibley is a student at Mt. San Antonio College.

(Anthony Mendoza

/

Courtesy Malcolm Sibley)

“Given the pandemic and everything people don’t really want to work right now,” said Serrano, a student at Santa Monica College, “and it’s easier to just post something on YouTube than it is to sit and make a video yourself.”

Mount Malcolm Sibley, a student at San Antonio College, agreed to make it a little easier with “ghost professors.”

“Always give professors the benefit of the doubt,” Sibley said. “They had to make the transition to online teaching and an environment they are probably not used to,” he said.

Sibley’s empathy could soon be put to the test as many colleges decide to have a large portion of their courses online for the fall semester.

What questions do you have about studying at a university?

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez focuses on the stories of students trying to overcome academic and other challenges in order to stay in college – with the goal of creating a path to a better life.

Ask him here

source https://collegeeducationnewsllc.com/college-students-ask-whats-up-with-my-ghost-professor/

No comments:

Post a Comment